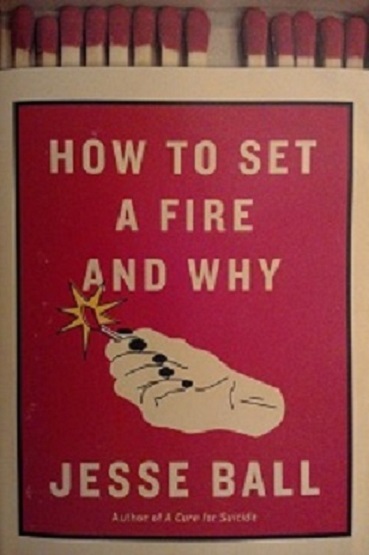

UNITED STATES—Jesse Ball continuously asks us a question in his new novel “How To Set A Fire And Why?”

Why does Lucia desire to burn things down? She’s an impoverished high school student with a keen mind and smart mouth. She is troubled by her mother’s institutionalization, father’s death, miserable school life, and tough financial situation with her loving, caretaker aunt.

The journey through this girl’s life and mind is a beautiful, enraging, postmodern anti- “the Catcher in the Rye” that captures some of the most fearful elements of our modern life.

Ball has a unique writing style. I often question the wisdom of writers who attempt fancy trick with form. Usually I take it as a sign that they’re trying to cover up a weak plot or characters with clever presentation. This is not the case with this novel. Ball tries uses some interesting techniques like using letters to create a map, use of blank space, single lines of text on a page, and the insertion of double column political pamphlets. All of this serves to show internal personal struggle and the formation of a political consciousness in a way that would be admirable to any of the great modernist writers. I have to say that this represents the best kind of postmodernism. It doesn’t present us with noise and confusion without solutions, but laments and sympathizes with the hardships of modernity. Where a writer like Murakami does this he’s usually showing the challenges and struggles of interpersonal relationships, Ball shows us the dehumanizing effects of modern capital and institutions.

As I reflect on the novel I keep coming back to that question.

Why?

Ball has presented us with one of the great critiques of American schools coming from the perspective of the outcast. Lucia is a loner. She has a high intellect and capacity for kindness, but she rarely speaks to others. Her teachers and administrators do little to better her situation. They blame her for offenses she has not committed. They punish her patronizing, demeaning visits to the school psychologist. Ironically, the only real attempt we see at helping her is undermined by the school’s principal who is all too willing to believe the worst about her. Ball has captured better than anyone I have yet read the frustration of being trapped in a school where you are both social outcast and enemy of the state. Her bubbling frustration, anger, and despair is superbly captured. If you’re a student this is required reading if you find yourself under the thumb of petty tyrants and bureaucrats.

Still we must search farther for the answer.

Why?

This novel rejects the solipsism that normally characterizes a lot of novels with a teenage, first person narrator. Holden Caulfield unfortunately occupies a preeminent place in American literature, and he is the first character we think of when we think of this genre. His wanderings through New York are filled with long, often hypocritical, self-centered ramblings. He longs for the past because he fears the hypocrisies of the adult world. His biggest great enemy is the “phony.” We get the impression that he is the biggest phony in New York City (add American literature,) and his own worst enemy.

Ball makes Lucia into a kind of anti-Holden. While she does indeed see joy in her past, she doesn’t waste her energy fruitlessly wishing to stop time. Instead she is more concerned with changing the world for the better where she can, and living well and authentically in the face of it where she can’t.

The novel is primarily a character study. This could cause pacing problems in the hands of a lesser writer. It doesn’t though. The novel has a rambling diary type feel. It’s not so far off from Stephen Chbosky’s “The Perks of Being a Wallflower.” Chbosky is a lot better than Salinger as well. At the very least Chbosky’s Charlie is a better person than Holden. He has the ability to see past his own problems, his problems being far greater than Holden’s, and empathize with the other people around him. Ball does Chbosky one better though. Lucia is not content to simply find good friends and a happy place in the world. As previously stated she wants to change the world. Ball certainly has created an admirable character, but he shows her to be complex as well. She has a great capacity for empathy, but as we see from her interactions with her classmate Stephan, a capacity for cruelty as well. Even the good among us can so often casually pass our miseries on to others. She is capable of eloquence and brilliance, but her Aunt reminds her and us that not all her anger and angst can be taken for wisdom. Yet another sign that Ball is far wiser than Salinger.

It’s pretty clear from early on that accepting the aging process, getting a good group of friends, finding that special someone, or any of the other normal resolutions is not going to cure all that ails Lucia. True she does get a best friend, and Lana is a fascinating character in her own right. She’s caring, but also crude, irreverent, direct, and hilarious (Lana and Lucia will both make you laugh). She’s the opposite of the magic pixie dream girl stereotype you find in a lot of young adult fiction. She is there for Lucia, and we can see how much her companionship means to our protagonist. Like I said it isn’t enough to fix everything though. To show the value of something without presenting it as a magic cure all is a sign of a good writer. Plus, you really got to hand it to Ball. He has the insight to add misogyny to the book’s litany of oppressions. Small comments and disgusting incidents dot the novel. It’s another thing that adds to Lucia’s sad state. It doesn’t have to be, yet it is. The more we see of Lucia’s situation the more we approach the answer.

Why?

It’s not so far off from that old Charlie Chaplin film “Modern Times.” No matter how much you try and move forward and better your situation, the forces of society continue to hold you back.

It’s not just the forces of modern society though. I get the distinct feeling that Ball has been reading his Camus. Lucia just keeps getting hit with tragedy after tragedy. Her father is killed, her mother is institutionalized, etc. There’s no notion of a universe where everything will work out for her in the end. We can be struck down any time. A car can come from nowhere and hit us. We can slip, fall, and meet our end. It’s hard enough to live in this world, but the hardships our institutions inflict make all this even worse.

This novel is another addition to the poetry of American poverty. Food insecurity constantly plagues Lucia and her aunt. Her licorice habit quickly goes from charming quirk to a sign of tragic circumstance. Some of Ball’s analogies for poverty in our society are stupendous. A game of dice shows us how hard it is to get ahead. A car being repossessed shows us the heartbreak of living at or below the poverty line. Most of all we see how this breeds anger. Anger hotter than white fire.

Fire has forever been stolen from Ayn Rand and her Objectivists. There is a quote in Atlas Shrugged.

“I like cigarettes, Miss Taggart. I like to think of fire held in a man’s hand. Fire, a dangerous force, tamed at his fingertips. I often wonder about the hours when a man sits alone, watching the smoke of a cigarette thinking. I wonder what great things have come from those hours. When a man thinks, there is a spot of fire alive in his mind – and it is only proper that he should have the burning point of a cigarette as his one expression.”

The objectivist sees fire as a symbol of conquest and power. For Ball it is a symbol of revolution.

“It is the visible aspect of man’s wit and cunning. It is the smallest and most complete mastery. To set a thing ablaze and thereby without effort change what it is-and cause light, and cause heat, and cause smoke.”

Rand could have written this herself, but just prior to this Ball is clear.

“This is not just a book about fire, although fire is our joy. It is a book about how we may share what is least, and the first step toward this sharing is that we must abolish the having of the most.”

Take that John Galt.

All mass movements are made up of people. Most of us desire to be happy with our lot. We wish to have enough to live decently. When a tough universe meets a cruel system anger is the inevitable result. When that anger goes unaddressed it leads to action.

“I am just the beginning of a long process,” Lucia says. “I am coming into a kind of inheritance. I can’t be the only one. There must be thousands like me.”

Why?

Using innovative form and fantastic characters Ball tells us why. People can take only so much. They will have food. They will have a decent standard of living. They will have equality and dignity.

Or else things will start to burn.