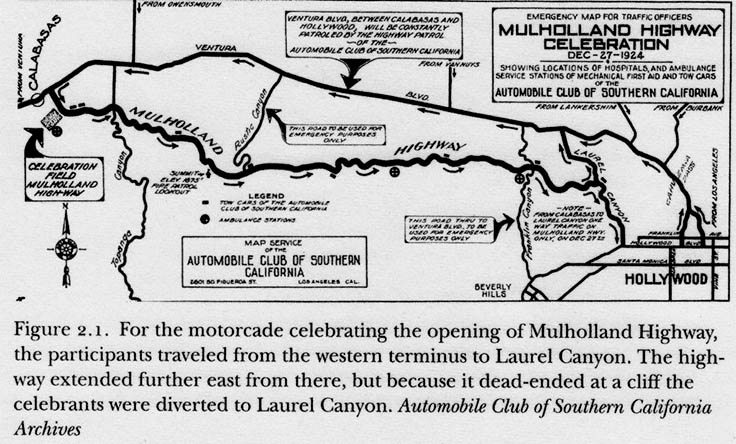

MULHOLLAND DRIVE —When we cruise along Mulholland Drive these days we are most taken by the scenic vistas, and the quiet beauty of the adjacent landscape. I was surprised to learn that most of the lore about the actual construction of the 22-mile roadway ignores the rough and tumble hard core dirty city politics that makes its existence even more amazing.

Opening on December 27, 1924, Mulholland Highway was a highly celebrated event for the City of Los Angeles. “The property in the district is owned by a small group of capitalists who expect to be rewarded for their enterprise by the subdivision of the frontage on the highway into building sites.”

The building of the roadway was so contentious that even after raising $1 million to fund the project, the Ventura Boulevard Chamber of Commerce petitioned the City Council on May 18, 1927 to shut the project down.

At the time the scenic parkway along the ridge crest of the Hollywood Hills was first conceived it was envisioned as the spine to a series of roadways over the hills which would connect the City of Los Angeles to the San Fernando Valley. By 1924, it was reported that every lot in the City of Los Angeles was in private hands. Speculators eyed the overpriced San Fernando Valley as the future.

At the time, city engineers were planning “Boulevardizing The City.” The automobile was not a “proxy vote against the Southern Pacific.” Street Assessment Districts to build new roads met with stiff opposition to the public taking of the right-of-way.

In contradistinction to the public and political grating and endless Court actions which plagued the building of other new roads in L.A., Mulholland Highway was rushed through the system. The project was completed within one year. Harry Merrick who had built several properties north of Mulholland was the driving force as the president of the Hollywood Foothills Improvement Association. DeWitt Raeburn, a veteran engineer from the Owens Valley Aqueduct project was put in charge. Raeburn submitted plans for the use of “construction camps.” He recruited a “commissary superintendent.” This was a project where fresh air and good food was considered an incentive for the 411 employees: 200 common laborers and 50 skilled workers. Merrick’s Hollywood Country Club was used as a staging area. Raeburn sought and was granted civil service exemptions for all of these employees; his permits were accelerated and frequent requests for exemptions where granted by the city council, claiming the project fell under the “emergency provisions of the city charter” to lay roads to fight wildfires. Expenditures of $149,000/ month were incurred for the massive earth moving portion, while $50,000 – $70,000/ month was spent thereafter. The Mulholland Highway Department enjoyed extraordinary autonomy.

While other parkway projects of the era included street lighting, planting and other amenities, the Mulholland project had none of these. Raeburn also knew, but neglected to tell anyone, that he was not installing water mains under the roadbed, even though that was common practice. In 1926, the estimate for putting in water mains came with a bill of $2.5 million.

While the project was touted to create the most traveled scenic highway in the nation, for the first three months of 1925 the official traffic count was a mere 750 cars per day.