NORTH DAKOTA—The Dakota Access Pipeline has gained national attention in recent months as thousands of protestors, activists and Native Americans have flocked to North Dakota to stand with the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe in opposition of the multi-billion-dollar pipeline, which is being built just a half a mile from Standing Rock Reservation.

Over 400 people have been arrested since protests began in January 2016. As pipeline construction nears completion, protestors and local authorities are trading accusations of aggressive tactics and civil rights violations.

What is the DAPL?

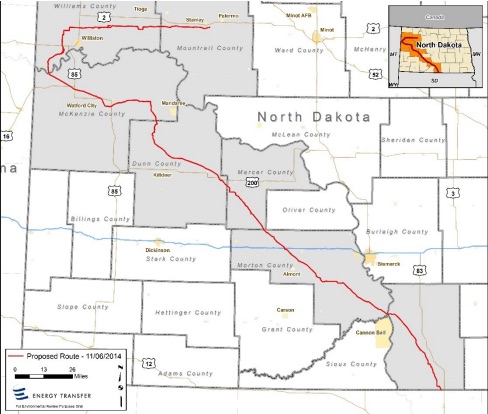

The Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL), or Bakken Pipeline, is a 1,172-mile underground pipeline that will stretch across North Dakota, South Dakota, Iowa and Illinois.

The pipeline—a $3.7 billion investment—will connect the oil-rich Bakken and Three Forks production areas in North Dakota to existing pipelines in Patoka, Illinois, and is projected to be ready for service by the end of 2016.

How did it get approved?

Iowa was the last of the four states that the pipeline would cut through to approve it in March 2016, leaving the DAPL with just one federal approval to gain: that of the United States Army Corps of Engineers (Corps) – the public engineering agency that has jurisdiction over domestic pipelines that cross major waterways.

The Corps approved the project to move forward in July 2016, despite three federal agencies’ formal requests not to do so – their decision relied on an environmental assessment prepared by the pipeline’s developer, Dakota Access LLC. The official assessment was published in August 2016 and constituted formal pipeline approval. The Corps defended the assessment in a statement and said it “contains an Environmental Justice analysis that conforms with recognized practice.”

Why is it being built?

The United States is the third-largest crude oil producer in the world, but its number one consumer, so it relies on foreign imports for half of the oil it consumes daily – which equates to approximately $388 billion in importations annually.

The North Dakota Bakken has seen a dramatic increase in its production of crude oil – large enough to eliminate the United States’ dependency on foreign crude oil imports, which would have tremendous economic advantages.

To address the massive transportation strains the increase in oil has caused.

North Dakota’s increase in crude oil production has created serious transportation strains in the Upper Midwest, particularly for industries like agriculture. Transportation shortages have caused rail car tariffs to spike from $50 per car to $1,400 per car.

Who opposes the DAPL?

The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe (Sioux Tribe) is comprised of about 8,000 residents who inhabit Standing Rock Reservation and has opposed the DAPL since its proposal in 2014. Activists have attempted to slow its construction on the grounds that the Sioux Tribe tribe relies on the Missouri River for drinking water, irrigation and fish.

Attorneys for the Sioux Tribe took their first legal step to block the pipeline to the courts on July 27, 2016, filing a complaint against the Corps alleging it “has taken actions in violation of multiple federal statutes that authorize the pipeline’s construction and operation.”

A federal judge denied the Sioux Tribe’s request for a “temporary injunction” on September 9, 2016 and then one month later, on October 9, a federal appeals court denied the tribe’s follow-up motion to appeal the September 9 ruling.

Senior officials from three different federal agencies raised environmental and safety objections regarding the North Dakota section of the pipeline.

In the months leading up to the DAPL’s final approval, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP) and Department of the Interior each individually called on the Corps to conduct an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) and more comprehensive analysis of the pipeline’s potential effects before moving forward with its construction.

Why is there opposition?

Standing Rock’s tribal headquarters—Fort Yates—is just 10 miles upstream the pipeline’s route. If the DAPL were to leak, over 19.7 million gallons of crude oil (the amount the DAPL would transport daily) could leak into the Missouri River and taint the tribe’s only source of water.

Since 2009, the annual number of significant oil pipeline accidents has shot up by almost 60 percent, according to data from the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration – and while pipelines are arguably the safest means of crude oil transportation (because rail spills occur twice as frequently), the effects of a pipeline spill are often more devastating.

In July 2010, corrosion created a 6-foot gash in a Kalamazoo River pipeline—Line 6B—and spilt 800,000 gallons of crude oil into the river, which seriously impacted its surrounding ecosystems, as photos from the incident’s Natural Resource Damage Assessment show.

The route was not coordinated with affected Indian tribes—a federal obligation.

ACHP regulations require federal agencies to consult and coordinate with Indian tribes if a proposed project could potentially compromise areas of historic preservation.

A March 11 letter from the EPA, a March 29 letter from the U.S. Department of Interior and a May 19 letter from ACHP cited several discrepancies in the Corps’ assessment, including its neglect to consult with the federally recognized Indian tribes who have “ascribed religious and cultural significance to the properties being affected.”

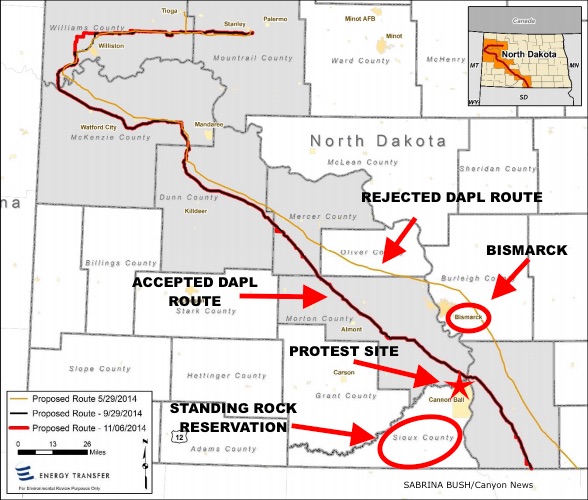

The original DAPL route was denied for safety concerns.

The original DAPL plan proposed a route that would cross the Missouri River upstream of Bismarck, North Dakota, but was later rejected for a number reasons, including: more road and wetland crossings; a longer pipeline; higher costs; and its proximity to the wellheads providing Bismarck’s drinking water. North Dakota Public Service Commission documents from 2014 show the original route upstream of Bismarck.

“They moved it down to Standing Rock, which is a very remote area, but people live at Standing Rock too,” said Jan Hasselman, an attorney with the environmental advocacy organization representing the Sioux Tribe, EarthJustice. “There is an environmental justice component here.”

So what’s next for the DAPL?

In a joint statement released by the Department of Justice (DoJ), Department of the Army and the Department of the Interior they requested the pipeline company—Energy Transfer Partners—voluntarily pause all construction activity within 20 miles east or west of Lake Oahe. Meanwhile, the Department of the Army will investigate concerns raised by the Sioux Tribe and determine whether or not it will need to reconsider any previous decisions under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) or other federal laws.

The pipeline’s construction is underway and slated to be completed within the next few months. Supporters of the DAPL—which include state and local government officials—have shown little interest in accommodating the project’s critics, including protestors on the ground.

Standing Rock and its supporters have shown no indication of backing down, vowing to continue fighting the DAPL through the subzero winter temperatures. Their persistence has sparked controversy between police and protesters, prompting allegations of civil rights abuse. On Monday, October 24, the Sioux Tribe formally requested that the DoJ investigate the ongoing law enforcement abuse allegations, which include excessive force and the unlawful arrests of peaceful protestors and journalists exercising their first amendment rights.